好文│收获 ~ 一个接触即兴的历史 by Nancy Stark Smith

Harvest — One History of Contact Improvisation

a talk given by Nancy Stark Smith at the International Contact Festival Freiburg, Germany, 2005

by Nancy Stark Smith

翻译:尹浩龙

译者注:前段时间翻译了Nancy Stark Smith在2005年弗赖堡艺术节的一个讲座,这段时间在组织大理的接触即兴艺术节,想分享给组织团队和老师,去思考为什么做艺术节,组织艺术节的初衷是什么,从历史中,我们总是会获得很多的启发,也在这里把这篇译文分享出来。这篇文章出现在Contact Quarterly杂志2006年夏/秋刊,由Andrea Olsen编辑,我附上了英文原文,和我的译文。文中的图片是我加入的,然后斜体字是我的注解。

This talk appears in Contact Quarterly, The Place Issue, Vol. 32 No. 2, Summer/Fall 2006.

There are many histories of the same moment. Maybe from this we can gain perspective. So this, naturally, is my version of the story.

在同一个时刻,历史会以各种各样的方式被记录下来,或许我们可以从中得到不同的视角的解读,这里,我讲述的是我的故事。

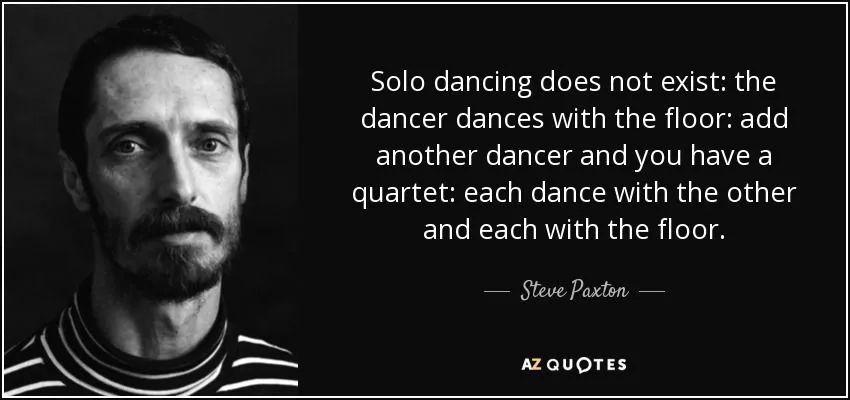

Contact improvisation was created by an American dancer and choreographer named Steve Paxton in 1972. Steve was born and raised in Arizona, and he brought many lines of movement training into his dancing. He was an athlete, a gymnast, a martial artist, and a modern dancer. He came to New York to study and danced with José Limón’s modern dance company for a while and with others—classical modern dance.

接触即兴,是由美国舞者,编舞家斯蒂文帕克斯顿(Steve Paxton)在1972年创立的,斯蒂文出生并成长于美国亚利桑那州,他受过体操,武术,现代舞等各种各样的运动训练,在他的舞蹈中,这些元素都有体现和影响。最早斯蒂文来纽约时,是在José Limón的现代舞团学习和跳舞,接触到的是非常经典的现代舞。

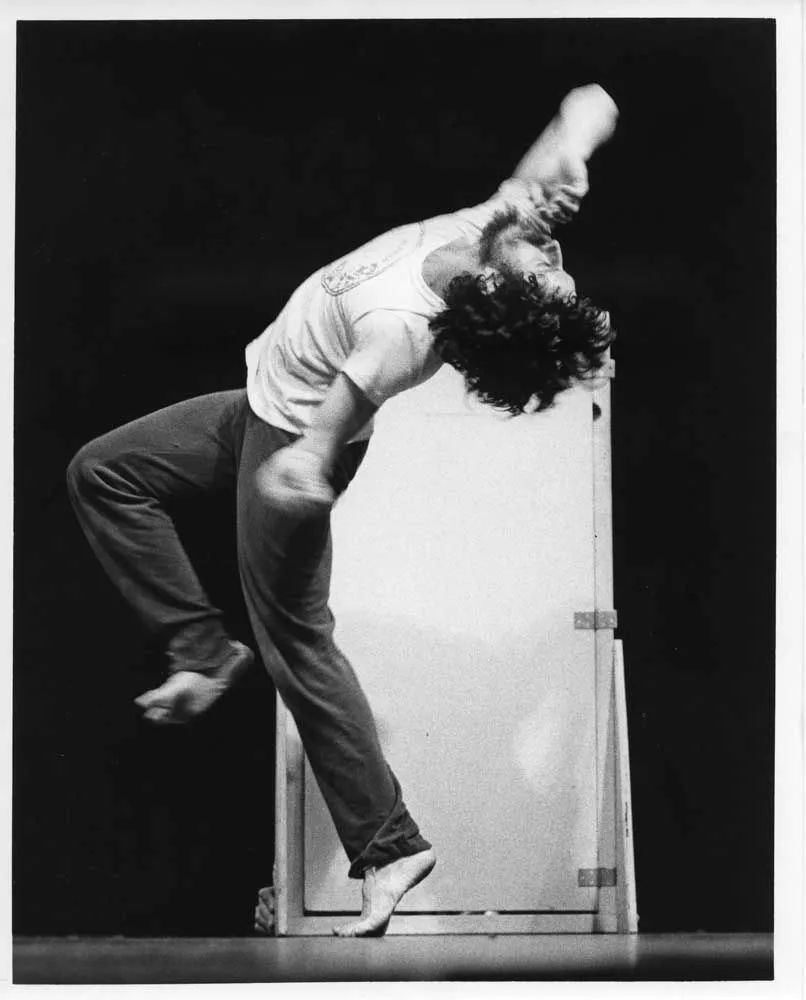

Steve Paxton

In the early 1960s, Steve danced in the company of Merce Cunningham, a revolutionary choreographer who was collaborating with musician/composer/ artist John Cage. Cage was influential in the development of new thinking and practices in dance and music in America and elsewhere. Cage asked his protégé Robert Ellis Dunn, an accompanist for Martha Graham, if he would teach a composition class at the Cunningham studio for the young professional dancers.

在60年代早期,斯蒂文开始在摩斯·肯宁汉(Merce Cunningham)舞团跳舞,当时肯宁汉是一个非常有革命性的一个编舞家,他和音乐家/作曲家/艺术家约翰凯奇(John Cage)合作,凯奇在舞蹈和音乐方面的创新思考是有深刻影响力的,他让他的门徒Robert Ellis Dunn,一个为Martha Graham伴奏的音乐家,来在肯宁汉的工作室为年轻舞者教关于舞蹈结构的课程。

Bob Dunn encouraged the dancers to open their thinking about dance and art. What kind of movement can be in a dance? Where does a performance take place? Where does the audience watch from? What kind of lighting or sound situation is involved? He encouraged them to try new things.

Bob Dunn在课程中鼓励舞者打开他们关于舞蹈和艺术的思考,什么样的运动可以叫做舞蹈?表演在什么时刻发生?观众是从什么地方观看?灯光和声音是怎样参与到演出当中的?他也鼓励大家去尝试从来没有做过的事情。

Robert Ellis Dunn作为一个音乐家,给舞者的这个结构课程成为了影响整个后现代舞发展的重要一环。

For their homework, they made many different pieces—Trisha Brown made a dance that happened simultaneously across several rooftops in Manhattan. Lucinda Childs made a piece in which the audience, in a loft studio, was instructed via audiotape exactly what to look at down on the street while dancers, stationed on the sidewalk amidst the pedestrians, pointed things out. Nowadays this doesn’t seem very radical, but at the time it really was! Steve made a piece with a large group of people doing the “small dance” (that many of us practice in contact)—the small reflexive movements that happen while standing still. It was called State

他们的作业,就是创作不同的片段,崔莎·布朗(Trisha Brown)做了一个作品,在曼哈顿的不同屋顶同时发生的舞蹈,Lucinda Childs的作品是在一个公寓中放置了一个提前录好的磁带录音,录音会清晰准确地告诉在场的观众去观看什么,楼下的街道上,舞者们在人行道上和行人混在一起,不断指示出一些东西。现在看来这些作品并不算激进,但在那个年代的确是很先锋。斯蒂文的作品是和一大组人做所谓的“小舞蹈”(small dance),在站立的时候去观察微小的肌肉反射引发的运动。

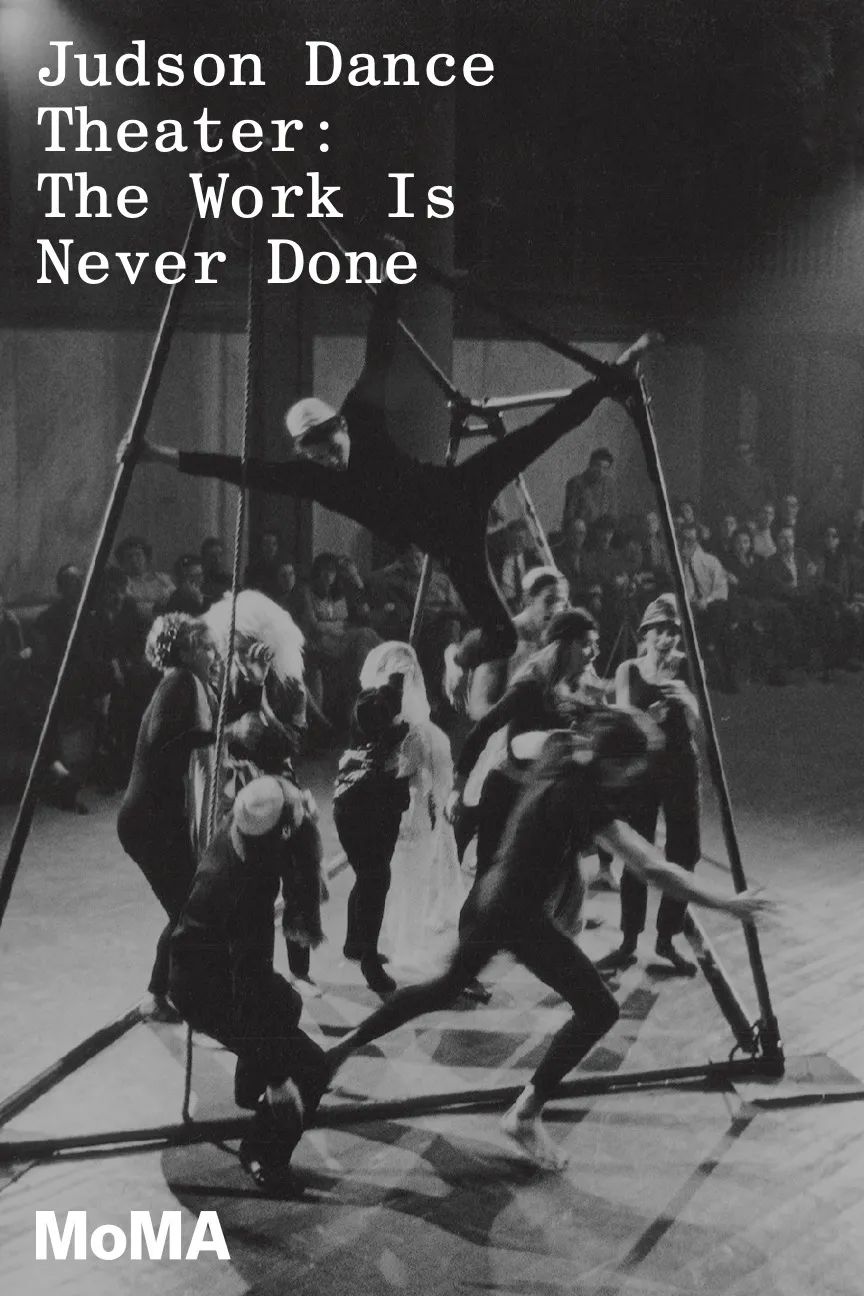

The dancers in Bob Dunn’s class came up with many interesting experiments and were very excited by each others’ propositions. They wanted to share their work with the public and looked for a place to perform. The minister at Judson Memorial Church in downtown NYC welcomed them to use the gymnasium in the church. From 1962 to 1965, the “Judson Dance Theater” produced many exciting evenings of performance there.

在Bob Dunn课堂上的舞者们都被彼此的创意启发,他们想要向公众展示这些作品,最后纽约市中心的朱德森纪念教堂(Judson Memorial Church)的管理人员同意他们使用教堂的体育馆来做演出场地。在1962年到1965年间,这个空间被叫做朱德森舞蹈剧场(Judson Dance Theater),在这里的夜晚催生和孕育了许多让人耳目一新的演出。

几年前MoMA为朱德森舞蹈剧场专门做的一个回顾展海报

朱德森纪念教堂的内部空间

This period opened up new possibilities for what kinds of movement—pedestrian, athletic, etc.—could be material for dance. Yvonne Rainer, an important artist in this dance revolution, made a project called Continuous Project —Altered Daily. Steve was in this group. One aspect of the project questioned leadership, and by the end, Yvonne wasn’t the leader any more; it had become a collective. This project evolved into the Grand Union—a dance/theater/ improvisation group that included Steve Paxton along with Yvonne, David Gordon, Trisha Brown, Barbara Dilley, Douglas Dunn, Nancy Green, and others. They made spontaneous performance. The members were dancers in various companies, but when they came together as the Grand Union, they had no plan, no set choreography. They used anything and everything on hand—props, lighting, music, text, costumes, movement—to build their improvised dance theater.

这段时间的演出探索了舞蹈的素材和来源的新可能性,什么样的运动可以成为舞蹈,包括行人走路,运动员的运动,等等。伊冯娜·雷纳(Yvonne Rainer),一个在舞蹈历史上非常重要的艺术家,发起了一个叫做Continuous Project—Altered Daily的项目,斯蒂文也参加到了这个项目中,这个项目的一个方面就是去质疑领导性,以至于到最后发起人伊冯娜·雷纳也没法继续领导这个项目了,它变成了一个集体合作创作。这个项目到最后发展成了一个叫做大联盟(Grand Union)的由舞者/剧场者/即兴者组成的团体,团队成员包括斯蒂文,以及伊冯娜·雷纳, 大卫格登(David Gordon),崔莎·布朗(Trisha Brown), 芭芭拉狄立(Barbara Dilley), 道格拉斯顿(Douglas Dunn), 南希格林(Nancy Green)等等.

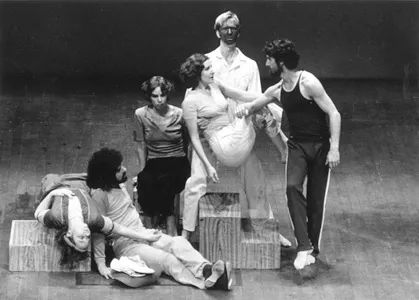

斯蒂文在大联盟1975年的演出

大联盟的演出

As a child and teenager, I was an athlete and a gymnast. Dance was not very interesting to me—I’d see the dancers standing in front of a wall of mirrors looking at themselves and making little movements. I didn’t understand what was exciting about that.

我成长过程中一直都是运动员,并练习体操,舞蹈对我来说并没有什么吸引力,我常常看到舞者们站在一面墙的镜子前观看他们自己,并做出一些动作,我并不能理解其中的魅力。

When I went to Oberlin College, in Ohio, in the early 1970s, this opening up of the dance field by the Judson Dance Theater had just occurred. In college I still did some gymnastics, some sports, but the emphasis was more and more on competition, and I became less interested. I thought maybe I was going to be a doctor like my father, but I knew I would always be moving and writing somehow.

在70年代初期,我去俄亥俄州的Oberlin College读书,那时候朱德森舞蹈剧场在舞蹈中做出的创新刚刚拉开帷幕,我在读书的时候还是练习体操,一些运动,但越来越偏竞技方向,我也越来越丧失兴趣,我总觉得我应该像我父亲一样成为一个医生,但我也知道我内心还是喜欢运动和写作。

During my first year of college, there was a January term project in dance, and someone suggested I try it. It was a monthlong residency with Twyla Tharp and her company, including classes, rehearsals, and performances. Twyla’s work was avant-garde and just starting to become better known. She used a wide variety of movement, and the training was physically and mentally rigorous. I got excited by what dance could be from working with her. The director of the modern dance company at Oberlin, Brenda Way, saw me in this residency and asked me to join the company. For the next year, I trained daily in modern dance techniques, performed, and began to choreograph.

在我大学的第一年,有一个一月份的学期项目是关于舞蹈的,有朋友建议我去试一下,这是一个在Twyla Tharp的舞团为期一个月的驻地项目,包括课程,排练及演出。Twyla的作品很有革新性,也慢慢为人所知,她会使用非常多的动作模式,训练也是非常累的,在和她的排练中,我对舞蹈的可能性大受启发,Oberlin的现代舞团的团长,Brenda Way,看到了我在舞团的表现,邀请我加入舞团,于是在之后的一年,我每天都在那里训练,学习现代舞技巧,表演,并慢慢接触到了编舞。

The following year, 1972, the Grand Union was invited to Oberlin College for the monthlong January residency. Each company member taught a technique-type class in the morning and a performance class in the afternoon. Steve’s morning class was at 7 a.m., and it was dark and cold. He called it the “Soft Class.” We would come into a beautiful old wooden men’s gymnasium, and there would be a chair at the door with a box of Kleenex and a little plate of cut-up fruit. You took a tissue and a piece of fruit and came into the gym. Steve led us in standing still, the small dance, while we kind of fell asleep and woke up, and also did some yoga-like breathing exercises. Then you’d blow your nose and eat the fruit, and after an hour, the sun came up and that was the end of the class. My mind was definitely opening. I had no idea what we were doing but I was curious and somehow very moved.

之后的一年,1972年,大联盟(Grand Union)受邀来到Oberlin College,并举行了一个为期一个月的驻地项目。每一个团队成员都在上午教一节技术类的课程,然后下午教一节关于表演的课程。斯蒂文的课是上午七点就开始的,天还是黑的,也很冷,他起了一个名字,叫做”柔软的课“(Soft Class),我们进入了男生的体育场,里面是非常漂亮的旧木头铺设的,在门口有一个椅子,上面是一盒Kleenex牌子的卫生纸和一小盘切好的水果,每个人可以拿一张纸巾和一块水果,然后进入体育场,斯蒂文带领我们安静地站着,做小舞蹈,我们都在一个似睡非睡的状态,然后我们也做了一些和瑜伽很想的呼吸练习,然后你可以吹出你的鼻涕,吃掉水果,一小时后,太阳出来的,课程也就这么结束了。我感到我的心智又被打开,我完全不知道我们做的是什么,但我很好奇,在某种程度上被感动了。

The performance class Steve taught in the afternoon was for men only. They used a very large, old, dusty canvas tumbling mat in the gym. Steve had also been practicing aikido, tai chi, yoga, and meditation. He had been to Japan with Merce and there, as well as in New York, had been exposed to Eastern practices. This was all coming into his dancing and dancemaking.

下午斯蒂文教的表演课只让男生参加,他们用了一个非常大,陈旧而布满灰尘的弹跳垫子,斯蒂文一直有练习合气道,太极拳,瑜伽和冥想,他和摩西肯宁汉一起去过日本,也去过纽约,所以对东方的传统习练很熟悉,这些都可以在他的舞蹈和舞蹈创作中能够看到。

Steve talks about his work with the men in the Fall After Newton video. He says he was training the men “in the extremes of orientation and disorientation”—standing still and experiencing the small dance of balancing, and then practicing big falls and rolls, like aikido rolls.

斯蒂文后来在牛顿后的跌落视频中有谈到他和这些男生的练习,他说他想要训练他们在一个“极端的位置和失衡的情况下”去保持一个稳定的站立,并去体验身体内平衡过程中的小舞蹈,然后是练习大的跌落和翻滚,比如合气道滚。

At the end of the month, Steve made a piece with the men called Magnesium, performed in the gymnasium on the mat. The audience watched from a running track above. The men began by standing still and then started to fall off balance—falling through the space, spilling onto the mat, rolling, getting up, with little soft collisions, slides, falls —staggering around the space like they were drunk or something, a beautiful fountaining of men, for maybe ten minutes, and then they finished with more standing.

在一个月结束后,斯蒂文和这些男生一起做了一个表演,叫做镁元素(Magnesium),这个表演是在体育场的大垫子上进行的,观众从上方的一个跑道上观看。这群男生开始的时候是稳定站立,然后慢慢从失去平衡跌落,在空间中落下,撞落到垫子上,滚动,然后起身,有一点点的轻度冲撞,滑行,跌落,在整个空间中进行,好像他们都喝多了酒,一群美丽的醉汉,一切进行了有大概十分钟,最后以站立结束。

Fall After Newton,这则短片记录了当时欧柏林学院的这些演出。

I was in the audience and was very moved. Magnesium, the Soft Class, lots of new ideas about performance from David Gordon, Yvonne Rainer, Barbara Dilley—my mind was stretching. After Magnesium, I mentioned to Steve that if he ever worked like that with women I would love to know about it.

我当时在观众中观看了这个演出,很受感动,镁元素,柔软的课,从David Gordon, Yvonne Rainer, Barbara Dilley等人产生的关于表演的新想法,都在不断拉伸着我的头脑,镁元素演出结束后,我问斯蒂文他有没有和女生也有这样的合作,我很有兴趣了解更多。

Steve went to teach at Bennington College in Vermont that spring of 1972 where he continued to develop his ideas from Magnesium. He got a small travel grant and decided to bring a group together in New York City in June of 1972 to do a performance project. He invited some young dancers that he had met in his travels as a guest artist—at Oberlin (Curt Siddall and me), the University of Rochester (Daniel Lepkoff, David Woodberry, and others), and Bennington (Nita Little, Laura Chapman, and others)—as well as a few of his colleagues in New York City.

1972年春天斯蒂文在佛蒙特州的本宁顿学院(Bennington College)教课,他在继续发展他在镁元素演出中的想法,在当年6月,他得到了一小笔奖学金,决定邀请一群客座艺术家去纽约准备一个演出,受邀者主要是他在旅行中遇到的一些年轻舞者,Oberlin的Curt Siddall和我,Rochester大学的Daniel Lepkoff, David Woodberry等人,来自本宁顿学院的Nita Little, Laura Chapman等人,以及他在纽约的几个同事。

We worked for one week in a loft studio in New York with a small blue wrestling mat. We worked all day, practicing a few things for a long time—like the small dance, during which Steve suggested different images of the skeleton, the flow of energy, the expansion of lungs; identifying small sensations. We also practiced a lot of rolling techniques—forward, backward, aikido, invented rolls, handstand-rolldowns—in order to be comfortable falling and rolling in different directions.

我们在纽约的一个小的工作室的一个蓝色摔跤垫上一起工作了一周,每天整天都在工作,用很长的时间去练习很少的几件事,比如小舞蹈,斯蒂文建议了给骨骼的不同的图像,能量的流动,肺部的扩张,识别微小的感受。我们也练习了很多的翻滚技巧,往前,往后,合气道,创新的滚,从手倒立往下的滚,都是为了让身体在不同方向去熟悉跌落和翻滚的过程。

Another thing we practiced: one person stands toward the back of the mat and everybody in turn runs and throws themselves at this person, who would try to catch them and somehow manage the weight. This usually meant going down to the floor together and rolling out of it. For hours: catch 1, 2, 3, 4…big people, small people. There would be people on the side to help, if needed, in the gymnastic tradition of “spotting.” We also did some head-to-head dances at this time.

另外一个我们练习的:一个人站在垫子的一端,其他人轮流跑过去,把自己的身体丢到这个人身上,这个人会尝试去接住丢过来的身体,然后找到重量的平衡。常常,这个过程就是一个共同跌落到地面,然后通过翻滚来结束。大量的时间,我们一个人一个人来,1,2,3,4,身材魁梧的人,瘦小的人,如果需要会有人在旁边做保护,就像体操传统中的“保护者”,我们也做了一些头对头的舞蹈。

At some point, we’d dance in duets on the mat: we’d try things, explore possibilities while improvising in contact. The others would watch intently. Sometimes the dances would last ten, twenty, thirty minutes. We’d watch for hours and then at some point you’d have a go. We were just figuring out what was possible, and we learned a lot from watching each other.

有时候,我们会在垫子上跳双人舞,我们尝试新东西,探索接触中去即兴的可能性。其他人会注意观看。有时候,舞蹈会持续十分钟,二十分钟,三十分钟不等。我们就这么几个小时地观看,一直到我们不得不离开。我们只是在弄清什么是可能的,我们从观看彼此学到很多。

Another line: video. In 1972, when Magnesium happened, video was just becoming portable. Cumbersome but portable. A man came to Oberlin to videotape the Grand Union performances and accidentally videotaped Magnesium, thinking it was the Grand Union. Steve saw the video and got very excited to have this feedback, so he invited the videographer, Steve Christensen, to join us in New York in June. So all of our practices and performances were videotaped. Every night we’d watch them in the loft where we were all staying. It was total immersion.

另外一条线索是,在1972年,当镁元素演出时,可携带摄影的出现,虽然还很笨拙。有一个人来欧柏林学院摄制大联盟的演出,然后很偶然地也拍下了镁元素,他以为这个演出也是大联盟演出的一个部分。斯蒂文看到了这个影像,非常兴奋,所以他邀请了摄影师Steve Christensen六月份来纽约拍摄我们。这段时间我们所有的练习和演出都有了视频的记录。每天晚上我们都在共同的居住地观看这些视频,完全沉浸在其中。

After one week of practice, we moved to an art gallery in downtown New York City—the John Weber Gallery—set up the mat and performed for five hours a day for a week. These were the first performances of contact improvisation. Steve made a postcard announcement—on the front was a picture of the Coney Island parachute jump, a ride at the amusement park. He also went to Chinatown and had fortune cookies made with a fortune that said something like, “Come to John Weber Gallery—contact improvisations,” and we gave them to everybody in the street.

一周的练习之后,我们搬到了纽约市中心的约翰韦伯画廊(John Weber Gallery),在那里放上了垫子,每天我们都演出五个小时,持续了一个礼拜。这是接触即兴的第一次正式公众演出,斯蒂文做了一个明信片去宣传,正面是是一张照片,Coney岛上的降落伞跳伞,在游乐园的骑行。他也去华人街做了幸运饼干,里面说的是,“来约翰韦伯画廊—接触即兴”,我们会去街上发这些幸运饼干。

When people arrived at the gallery, they might walk through and look for five minutes or sit down and watch for a while, maybe come back the next day. We practiced throwing and catching, the small dance, and duets—the dances were almost all duets in the beginning. Sometimes, when we wanted more space, we’d move the mat away. These performances continued for five days and then were over.

当观众抵达画廊的时候,他们可以四处走动,看五分钟,或者坐一会,再观看一会,明天他们或许又可以再回来,我们练习的是抛和接,小舞蹈,双人舞,舞蹈形式在开始的时候几乎都是双人舞,有时候,我们想要更多空间,我们会把垫子移开,这个演出持续了五天,然后结束了。

I often think that contact improvisation could have just been a piece that Steve Paxton made in 1972, and that was the end of it. Many artists get an idea, bring people together to rehearse, show it, and that’s it—on to the next idea. So the fact that we’re here today—33 years later, with people all over the world practicing contact improvisation—is very interesting.

我常想接触即兴就是斯蒂文1972年做的那个作品,然后就结束了。许多艺术家都这样从一个想法开始,将人组织起来排练,演出,然后就结束了,随后又继续下一个想法。我们33年后的今天坐在这里,和全世界各地的朋友一起练习接触即兴,是非常有意思的。

The dancers at the John Weber Gallery event went in different directions. I went to a summer retreat with the Oberlin Dance Collective and Nita went to a summer job teaching dance. Several of us were very turned on and wanted to continue exploring the dancing we had done with Steve.

在约翰韦伯画廊的舞者后来也在不同的方向发展,我和欧柏林学院舞团及Nita一起去了一个暑期项目,教授舞蹈。我们中的许多人都非常感兴趣继续探索和斯蒂文一起做的这个舞蹈形式。

The nature of this form is that you need a partner to do it, and I think this is one of the most important reasons it has spread. If you could do it alone, I don’t know how far it would have gone…. To get a partner, you have to make one; you have to find a way to communicate the form. Steve did not stop people from doing that—he didn’t say, “No, you have to get it from me.” So, many of us tried to share it, to create partners so we could continue to dance. And it started to grow.

这个舞蹈的本质要求你要有一个舞伴才能练习,我认为这一点是接触即兴得以广为传播的一个重要原因。如果你可以自己做,我不知道现在有多少人会知道它。为了找到舞伴,你需要和别人沟通这个舞蹈是什么。斯蒂文没有说每个人都得从他那里学习,他没有组织别人练习,我们中许多人都在和他人分享,为了有更多的舞伴我们可以一起练习,这样,接触即兴开始慢慢发展。

For the next few years, whenever Steve had a performance in New York or elsewhere, contact improvisation was often what he showed as his work. He would bring a small group together to perform—Nita Little, myself, Curt Siddall, Danny Lepkoff, and David Woodberry were regulars, plus a few others—in New York, on a California tour in January 1973, and on a tour to Rome (at L’Attico gallery) in June 1973.

之后的几年,当斯蒂文在纽约或者其他地方演出时,接触即兴常常就是他的作品,他会组织一群人一起表演,Nita Little,我自己,Curt Siddall,Danny Lepkoff和David Woodberry是最常出现在他的舞者名单上的人选,我们去了纽约,1973年1月去了加州巡演,然后在同年的七月去了罗马(在L’Attico画廊)。

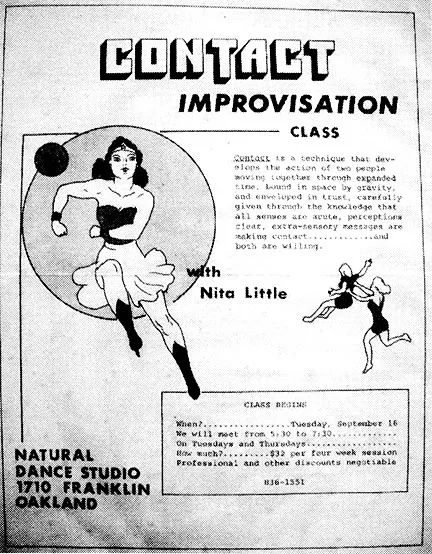

Three years later, in 1975, I had graduated college and was living in northern California. Steve called to ask if I would tour with him in the Northwest of the U.S. A few days earlier, I had been surprised to find a flyer on a wall in San Francisco that said, “Contact Improvisation!” with a picture of Wonder Woman. It was a class by Nita Little! (I hadn’t known she was in the area.) I suggested to Steve that we get together with Nita and Curt for a reunion, which we did, forming a company called Reunion that met every year for several years, with invited guests, to tour the West Coast, teaching classes and giving performances of contact improvisation.

三年之后,1975年,我从大学毕业,搬到了加州北部居住。斯蒂文打电话给我问我是不是愿意和他一起去西北部巡演,几天前,我也在旧金山的一个墙壁上看到了一个海报,上面画的是神力女超人(Wonder Woman),写着“接触即兴!”,这是Nita Little为她的课程做的海报(我都不知道她住在这里)。我和斯蒂文建议,我们可以约上Nita和Curt,大家可以再次见面,于是我们一起,组成了一个团队,起名重聚(Reunion),这个团队每年都会聚一下,和特邀嘉宾一起,我们巡演了西海岸,教课,表演接触即兴。

Nita Little当时在旧金山的神力女超人课程海报

At that first Reunion tour in 1975, we started to hear about people who had seen us previously and were now practicing contact. We also heard of some injuries…a few pretty serious. In our group, we had had bruises but nothing more serious than that. The safety issue really concerned us. There was some theorizing that our training —especially things like the small dance and the subtle sensing work—was keeping the bigger, more dangerous interactions balanced and safe. But people who just saw a performance would try the bigger, flashier moves without the other training.

在1975年的第一次重聚巡演中,我们开始碰到之前看过我们演出,现在在练习接触即兴的朋友,我们也知道有的人因此受了伤,几个人还伤得挺严重。在我们的团队中,我们也有一个瘀伤,但都不是很严重,于是安全的问题得到了我们的关注。我们的训练中,我们开始着重诸如小舞蹈和精微层面身体觉知的练习,这些练习让我们之后更激烈和危险的互动更平衡和安全。有的人只看到我们的演出,就忙着去尝试那些激烈,炫目的动作,而没有其他基础的训练。

So we thought that in order to keep it safe, we should copyright the work, so that you had to train with us to do it. We wrote up the papers and almost signed, but decided not to. I like to think that we could see our future and did not want to become the “contact cops” of the world—where we’d have to police contact and hear about someone teaching somewhere and check: “Do we know them?” And if not, tell them they can’t do it…

我们也讨论了是不是要为这个舞蹈形式申请一个知识版权,主要是为了维持其安全性,这样你需要来和我们上课才能学习这个舞蹈。我们文件和材料都准备好了,就在要签名之前,我们还是放弃了这个想法,我觉得我们都预想到了未来,我们不希望我们自己变成世界的“接触即兴警察”,我们需要不停去监视接触即兴,一旦听到有人教授接触即兴,就要去检查一下,我们知道这个老师吗?如果我们不认识他,我们就要告诉他,你不能这么做。

There was also the sense that if it’s exciting for people, they will do it anyway but just not call it contact improvisation, and so the coherence and connectedness of the developing work would be lost. So instead of copyrighting, we created a newsletter, where everyone who was involved could write about what was going on with them: “I taught here…this is what I’m learning”—invite people in instead of pushing them out. And hope that if someone was really working in a dangerous way that people wouldn’t participate. The worst would be that the work gets a bad reputation. But there was also a feeling that if you glimpse the seed of the work, you’ll find your way to some better information, hopefully.

如果这个舞蹈很受人欢迎,那人们可能就会换一个名字然后继续练习,这样我们丢掉了一个有连续性的关联的发展。取代注册知识版权,我们创建了一个通讯组,大家都欢迎来就接触即兴书写自己的经验,“我在这里教课,这是我在学的”等等,我们邀请大家加入,而不是把他们隔离在外。希望这个形式能让危险的练习方式减少,因为如果一个方式很危险,那大家就不会去参与,最糟糕的结果就是这个舞蹈变得名声不好,但我们也会觉得如果你得到这个舞蹈的核心感觉,那你会找到你的方式去学习更多。

So that was the origin of the Contact Newsletter, in 1975, which is now Contact Quarterly magazine (with a CI newsletter in it)—to encourage people to stay in touch and communicate about how they’re working. Lisa Nelson joined me as coeditor in the late ‘70s, and we’ve been editing and producing the journal together ever since.

这是我们在1975年创建接触即兴通讯的初衷,现在这个邮件组叫做接触即兴季刊杂志(Contact Quarterly),里面包含了CI通讯(CI newsletter),杂志鼓励大家保持联系,交流彼此的学习。70年代后期,Lisa Nelson加入了我一起负责杂志的编辑工作,我们俩从那时候就一直在一起工作。

After the first Reunion tour in 1975, the number of contactors grew considerably. Since then, many individuals have contributed significantly to the development of the dance form as practitioners, teachers, and performers. In addition, by the late 1970s/early 1980s, several notable contact companies had formed—Mangrove, Contactworks, Catpoto, Fulcrum, Freelance, and others—in San Francisco, Minneapolis, Montreal, Vancouver, and New York, each bringing its own distinctive approach to the body of work.

在1975年重聚巡演后,接触即兴练习者有了显著增加。从那时开始,很多人都为这个舞蹈的发展贡献了自己的力量,他们中有练习者,老师,表演者。在70年代末80年代初,有多个接触即兴舞团建立起来,包括Mangrove, Contactworks, Catpoto, Fulcrum, Freelance等,分别在旧金山,明尼阿波利斯,蒙特利尔,温哥华和纽约,每个舞团都带入自己对接触即兴的独特诠释和理解。

For me, our early performances were a showing of a phenomenon. From the beginning, people asked, “Well, is this dance?” Big question. It came from a dance-art mind and intention. It came at a time in American history, and probably world history, when established roles—of gender, authority, etc.—were being questioned. Part of it was a change in the way dance was made, that it could be made collaboratively. Also you had women lifting men; I didn’t think much about it then, but when we would show the work, people were amazed by things like that—by falling, by being on the floor, or by men being sensitive with each other, women being strong, people being a little bit out of control, and the pure physicality of it. People would see the work and get very excited and probably a little confused as well.

对我来说,我们早期的演出是一个现象的展示,开始的时候,人们问,这是舞蹈吗?很大的问题,它来自于一个舞蹈艺术的思考和使命,也在美国,及世界历史的一个时期,我们开始质疑确立起来的系统中关于性别,权威的地位,其中一部分是关于舞蹈编创方面的改变,可以由一个团队一起创作,你也看到女性托举男性,在那个时候我没有多想,但当我们演出的时候,观众对这些变化很惊喜,包括跌落,在地板上的活动,男性可以在彼此关系中更加敏感,女性可以呈现出强壮的力量,大家都有些不寻常,不受控制,以及整个舞蹈的身体性。观众在惊喜之余,可能也会有些困惑。

One time early on, Steve wanted to show the work to a few of his artist friends in New York. He and I danced at a downtown performance venue called the Kitchen. We showed a few video clips and demonstrated contact. Simone Forti was there and said, “Hmm, it’s kind of like an art sport.” We were excited about this term “art sport.” It temporarily solved some problems. That name was used quite a bit for a while.

早期的一个时候,斯蒂文想要把这个作品展示给他在纽约的几个艺术家朋友,他和我在市中心一个叫做The Kitchen的场地做了一场表演,我们播放了一些视频片段,示范了什么是接触,Simone Forti在现场,她说,这好像是一个艺术和运动的融合。我们都喜欢这个表达,“艺术运动”,这个表达暂时解决了一些困扰我们的问题,我们用了很长一段时间。

There’s no set pedagogy or certified way to teach contact. People learn a lot when they try to teach. Often they start by teaching what they were taught, then change things a little bit to fit the particulars of their students. They incorporate material from other work; they invent new things. This use of related material can sometimes cause confusion for students: how is contact distinct from Body-Mind Centering, or yoga, or other partnering forms, or release technique?

没有一套教学方法或者认证的方式去教授接触即兴,大家在尝试教学的时候也会学到很多,他们从教授自己学习到的东西开始,然后开始慢慢一点点做改变,以实现他们学生的状况,他们也带入了其他领域的知识和材料,发明了新的方法,这些和不同领域的交织可能会让学生有些疑惑,接触即兴和身心术(Body Mind Centering)到底是一个什么关系,或者和瑜伽是一个什么关系,和其他双人技术呢,和释放技术(release technique)呢?

Because of this freedom in teaching, people have created a lot of teaching material—principles, exercises, language, scores, formats. These become part of the canon, and that’s wonderful; but it can create a problem if you think you have to get good at all these techniques before you can do contact improvisation. That’s not true. Once you get a clear feel for the basic premise, develop a few safety skills, and get your reflexes primed and ready, then you’re off. You learn by doing.

因为这个在教学上的自由,人们也创造了很多教学材料,原则,练习,语言,舞谱,形式。这都变成了这个系统中的一部分,这是很棒的,但也让人会觉得如果你要做接触即兴,你得把这些所有的技巧都学会,这不是事实,一旦你有一个基础的认识,学习了一些保证你能安全的技巧,让你的条件反射机制准备好,然后你就可以开始了,你会边做边学。

Often teachers teach what they like or what they’re good at. They create an exercise to show how they do what they do—to give you easy access to it. There’s a lot of teaching material now —sluffing, surfing, this and that lift, a lot of principles and vocabulary. The issue is how to digest it and improvise, because improvisation is an essential part of the work—not just to learn steps or moves and put them together, but to meet, make, discover, and be curious.

通常,老师会教导他们喜欢的,或者他们擅长的,他们创造一些练习来展示他们做的是什么,如何去做,这样学生会更容易理解,现在有很多的教学材料,坍塌(sluffing),冲浪(surfing),各种各样的抬举,许多的原则和词汇,但问题是你如何消化这些材料,如何去即兴,因为即兴才是核心,而不是学习这些步骤和动作,然后尝试把它们组合到一起,而是去遇见,创作,发现和保持好奇心。

Jams: This was a new phenomenon. I mean, you don’t have modern dance jams or ballet jams. Usually in the contemporary dance world, you have class, rehearsal, and performance. I think the jam model came from Steve’s experience with the martial arts and the dojo mentality of people at different levels training together. It answered the question of how to keep practicing. Maybe someone set aside two hours on a Sunday to practice with a few people. And then another thinks, “Oh, this is great. Let’s go away to a hot springs where we can soak in the mineral water, take saunas, and dance all day.” “Nice idea, let’s do it for a week. Let’s start with a led warm-up,” etc.

舞酱,是一个新的形式,我的意思是,在现代舞或者在芭蕾中,你没有舞酱这么一个形式。通常在当代舞的世界里,你有课程,排练和表演,我认为舞酱这个形式来自于斯蒂文的武术经历,在武术中不同水平的练习者都在一个场地一起训练。这也回答了如何练习的问题。大家可以在周日空出大概两个小时的时间,然后一起练习,然后一段时间后,可能有人提议,我们去泡温泉吧,然后蒸个桑拿,然后我们跳一天的舞,再过一段时间,有人提议,我们可以做一个礼拜,等等。

The Breitenbush Jam in Oregon was one of the first retreat jams, at a beautiful, remote hot springs. After a few years, there wasn’t enough room for everybody that wanted to come, so another jam started at the Harbin Hot Springs in California. And then the East Coast people didn’t want to have to travel so far, so they made an East Coast Jam. And then festivals started and facilities (like Arlequi in Spain and Earthdance in Massachusetts) began to offer regular CI workshops and events.

在Oregon的Breitenbush舞酱是第一个以静修形式举办的舞酱,在一个很漂亮而偏僻的温泉,几年之后,这个地方就人满为患,于是他们又在加州的Harbin温泉找了个新地方,东海岸的朋友不想要旅行那么远,之后又了东海岸舞酱。之后艺术节的形式开始出现,(比如西班牙的Arlequi,和Massachusetts的earthdance)都开始经常性举办接触即兴的工作坊和活动。

Since there’s no teacher certification, the way that teachers stay current is to meet each other, have conferences, ask questions, create dialogue. Instead of arguing over an official interpretation, teachers are encouraged to communicate with each other, and a number of teacher conferences and exchanges have developed.

因为这个形式没有认证老师,老师们通过和彼此的交流来获得最新的资讯,举办会议,问问题,创作对话,与其就一个问题争吵不休,我们鼓励老师们去和彼此交流,发展出了很多的教师会议和交流活动。

Throughout contact’s development, a gentle anarchy has prevailed over its “organization”—with individuals freely pursuing their interests and local and regional associations forming to support organized activity.

在接触即兴的发展中,无政府状态压倒了“组织机构”,个体能够充分自由地找寻他们的兴趣,本地和地区的社群支持和组织活动。

I think some problems might arise from not having a certification, but at the moment it seems more beneficial to the form to have people be free to contribute their creative energy to it. It adds tremendous value to the work.

没有认证老师会有它的问题,但目前来说,对于接触即兴更有用的是让大家都能把自己有创意的能量放进去,这为其增加了无数的价值。

(全文完)

六月活动

图片来自www.globalunderscore.com